Special Web Offer - Get 50% OFF!

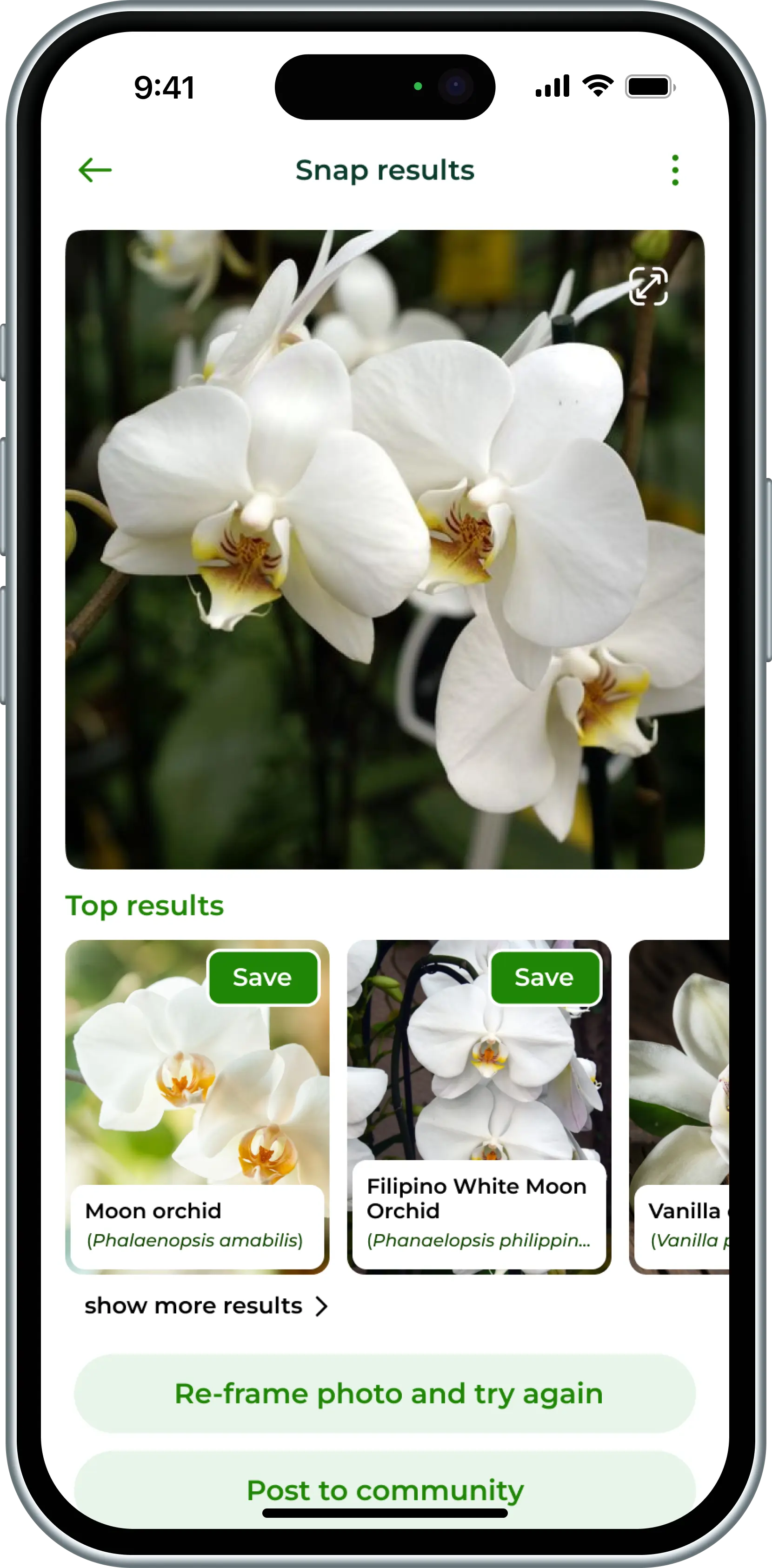

Grab Your Deal NowInstantly Identify

Any Plant

Capture, snap, and learn in seconds. Discover detailed information, curious facts and become a plant expert on the go.

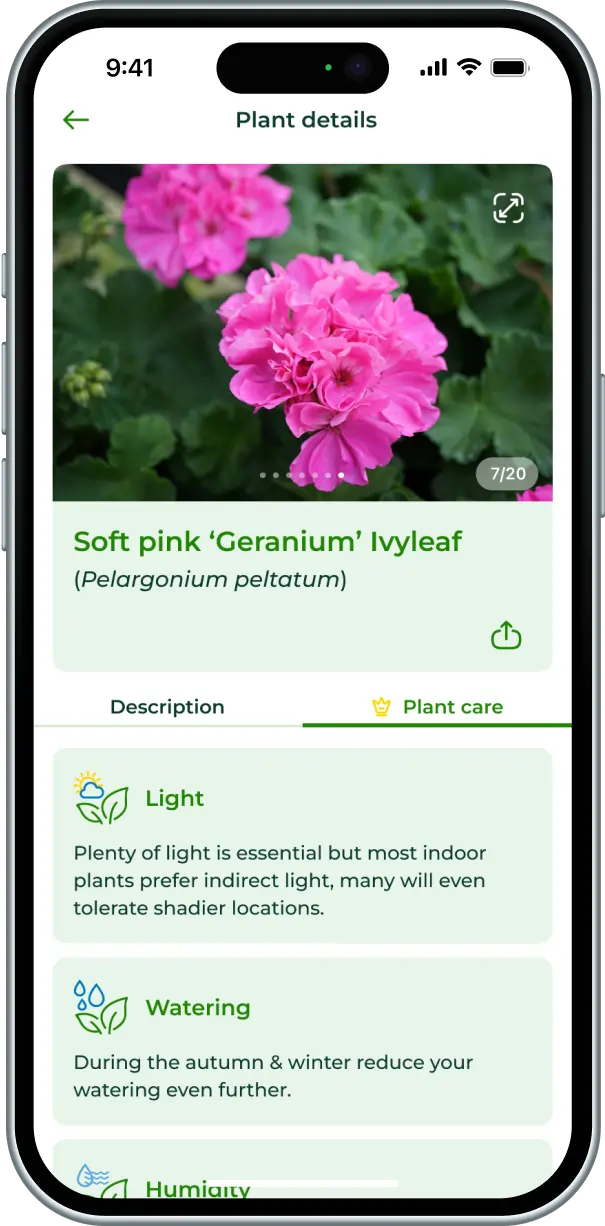

Nurture Your Plants

With Care

Get personalised care tips tailored for your plants' unique needs. From watering schedules to light conditions, keep them thriving with ease.

What disease do my rose leaves have?

Lilith Jones

Look at this gorgeous color! I can't believe I managed to grow this in my garden

3 hours ago from Glendale, CA